The idea behind this article comes from my interest in two topics: the status of women, and the region of southwest Asia (aka SWA, an expression I prefer to “Middle East”, as the latter comes from a colonialist point of view). In a context of media attention and progressive awareness of the pressures and violence inflicted upon women, it is easy to assume that society is on the verge of achieving respect and gender equality, at least for European countries, and that current claims stem from ungrateful and radical feminist women.

To offer a current snapshot of the situation, I wanted to give the women who live in Europe and in SWA a chance to speak, so we can hear about the effect their gender has on their life experiences, according to their work and social environment. Through their testimonies which identify the obstacles they face, I aim to mobilise collective intelligence, to gather ideas to improve and, ultimately, change things. Because there is still a long way to go. And whether you are a man or a woman, you have a part to play too!

@

Some definitions

Sexism: according to the Cambridge dictionary, it is (actions based on) the belief that the members of one sex are less intelligent, able, skilful, etc. than the members of the other sex, especially that women are less able than men.

Sexual harassment: according to the same source, it is unwanted or offensive sexual attention, suggestions, or talk, especially from an employer or other person in a position of power.

It takes place:

1. In the public space, in the form of verbal, physical and/or sexual assault (insults, threats, exhibitionism…) preventing women from being completely safe.

2. In professional settings, through sexual remarks and behaviours which undermine the rights and dignity of a person, and can alter mental and physical health and/or compromise their professional future…

3. In the private sphere, exposing women to violence such as sexual exploitation, domestic violence, rape, forced sterilisation, forced marriage, mutilation (excision), femicide, honour killing, stoning, sexual violence in time of war, … The article will not cover these cases.

We should also mention intersectional violence: violence that combines several criteria such as gender, skin color or sexual orientation. They undermine these minority groups and amplify their discrimination.

© emmy·in·the·mix

Sources, in order: WHO (2021), HCE (2019), Arab Barometer (2018-19), franceinfo (2018), ONU Women (2013).

Survey methodology

A total of 22 women aged 26 to 88 years old living in Europe or in the SOA were interviewed on the basis of a common questionnaire between March and May 2021. Three methods of data collection – face-to-face, by telephone and online – were combined. Results are presented thereafter so that they are representative of women in both regions, the SWA sample being smaller (28% of total sample). In order to preserve their anonymity and in agreement with them, women will be quoted using an initial, their age, and their current place of residence.

Before we begin, it is important to clarify that the following testimonies come from a sample of women who are not representative of the feelings or experiences of all women. They are educated, have access to social media and are aware of the issue of gender inequality. In addition, the situation is not homogeneous within the two regions or even within countries. However, it is important to listen to every single point of view, which is valid and relevant.

@

1. Do you think that your society is sexist?

Although all SWA societies are intrinsically different and the degree of sexism within them can vary, the answer is unanimous: 100% of women in SWA answered yes. How do they realise that they are being discriminated against? They observe a lack of autonomy and a certain control exercised by men over their life.

“Very. Women in the Middle East – based on personal experience – tend to struggle a lot with things such as making their own decisions/choices, voicing their honest opinions, dressing the way they want, basically doing anything that doesn’t involve “approval.” – B., 24, Oman.

@

“I think globally there’s still so much to be done for gender equality and sexism, and the Middle East is heading in the right direction but right now, it definitely stands as sexist, more so than Europe. Even with the smallest things, such as being underestimated with our driving skills because we’re a “woman”, or slight flirting gestures at the office because we choose to dress fashionably (yet still covered).” – T., 26, Qatar.

@

“I never experienced so much sexism in my life. It is a constant struggle here. Of course there is sexism too in Europe, but it is much more indirect and hidden.” – K., 30, (born in Europe), Egypt.

@

In Europe, 75% of women think their society is sexist. There is a generational shift though: discrimination was once deemed normal and unalterable, something women had to live with. It is now gradually perceived as a cultural trait to be eliminated.

“Not at all, not at work. But they are paid less than men. It has always been this way. Since I was born, men have always been luckier than women. It’s down to our history, women have always been the men’s maids, in charge of the house.” – M., 88, Switzerland.

@

“For me sexism is institutionalised/cultural, a bit like racism. The wage gap, the small number of women in senior positions, the lack of enthusiasm around inclusive writing or the feminisation of certain job names show that our culture is still sexist today.” – F., 32, UK.

2. Have you ever been harassed in the public space because you are a woman?

Unfortunately, 91% of the participants answered yes, across both regions. This harassment includes “cat-calling, whistling and stalking, people trying to grab your behind, openly commenting on your features in multiple languages”. It is perpetrated by “young male teenagers up to older men. Soldiers, police, etc. is openly involved and if they see it on the streets, they cheer and clap hands. It happens every day in Egypt and unfortunately it is normal“(K., 30, Egypt).

This violence, which is very present throughout adulthood, begins even before adolescence:

“First time I was 12, it was stalking. I knew the guy, he was the same age as me. He walked behind me from the school to my place. And he continued. And he stopped after 2 years. My father told me not to say anything. I did not react, I ignored him. In the beginning I was scared but then I got used to it.” – R., 26, Palestine.

@

“Yes! But I think when I was a teenager, I experienced this type of harassment as a source of external validation (eg: a compliment) and it took a long time for me to realise that it was not normal.” – F., 32, UK.

@

European women are an easy target when they travel alone, because they are perceived by the locals as more promiscuous:

“Yesterday, when I went grocery shopping, one guy called me “Russian” which basically means here they think you are a prostitute.” – K., 30, Egypt.

@

“I have experienced more harassment when on vacation in North African countries: they call you, they want to touch you.” – C. 42, France.

@

In order to deal with this situation, in a patriarchal society and provided with lower physical strength which works against them, women’s main strategy is to ignore it:@

“Catcalling: I just ignored them. Even in subsequent times, I was ignoring, because it is difficult to stand up to the harasser in a conservative society.” – A. 26, Turkey.

@

“It has happened so many times that I am so used to ignoring remarks, not responding, and moving on without making eye contact. It almost comes as second nature to not engage with remarks from men.” – T., 26, Qatar.

3. Which is the most sexist environment?

Harassment, one of the gender-based forms of violence, does not only occur in the streets, in broad daylight.

In SWA, it appears that family teaches and perpetuates a patriarchal hierarchical structure where “men will almost always have the upper hand, power and control over the women in the family making them feel like minorities” (B., 24, Oman). The gender of newborns is very important and determines the child’s personal and professional future. Families are happy “when they get a new-born son because he will be man of the house, will stay with them, will take responsibility for the family and provide financially towards it. The girl will be ‘useless’ to them as she will ‘belong’ to her husband’s family” (R., 26 ans, Palestine).

This difference leads to segregation in the labour market, where “many professions are gender specific, for example female teachers for female students” (R., 26, Palestine). When women enter male-dominated fields, they must fight to prove they are legitimate:

“Law is dominantly practiced by men, I am kind of an ‘intruder’ in this environment. You can’t go to a particular court because you are a female, or it is not female friendly. A sexist attitude can sometimes lead to positive results, if the person you deal with likes women then you can go faster in a process.” – D., 30, Palestine.

@

Discrimination in the workplace is also identified by European women who consider it “particularly problematic because sexism is strengthened by abuse or inequalities of power” (C., 32, Switzerland). This environment favours men, who “work to provide for the family” (M., 88, Switzerland) and who are considered “more reliable: no pregnancy or sick child leave” (A., 40, France).

“At the Post Office back then, once you got married, you had to resign. Men were in charge of the Post Office, they sure didn’t want to have a pregnant woman at work. »- M., 88, Switzerland.

@

“No matter what the environment is. Access to working in operating rooms is made easier for young men. You often hear people say ‘don’t get pregnant during this semester…’, or even during the whole boarding school if you want to be successful…” – A., 40, France.

@

In Europe, sexism can be found in the sports world, in “contact sports, known as violent, in which many people use negative feminine and/or homophobic terms to indicate what they are not, and make their actions seem more masculine… As if violent contact meant masculinity…” (A., 34, France).

Finally, religious institutions, with an almost exclusively male hierarchy, show some degree of sexism:

“I am thinking of the religious environment, because many beliefs are based on interpretations of the divine message which are, in my eyes, inaccurate/distorted, and religions most often are made of rules set by men, through their point of view. Probably a logical continuation of the law of survival of the fittest, always.” – S., 44, France.

4. Sexist remarks: the best 12

I asked participants to remember the most sexist remark they had ever received. Most of them revolve around gender stereotypes, where women are judged by and confined to their beauty, and considered fragile.

1. “Don’t cry, you are not beautiful when you cry.” – C., 32, Switzerland.

@

2. “Wow! You count fast for a woman!” From a salesman who was amazed that I could count so quickly in my head because, I quote, “Women are not as good at maths.” – A., 34, France.

@

3. “A colleague of mine asked me: ‘How is it possible that a married woman has gone to another country for several years without her husband?’” – R., 31, France.

@

Women mentioned that their professional success is considered to be proportional to their physical appearance or their masculine side, not as a result of their work or their skills:

4. “Just before a professional interview, my ex told me (in more vulgar terms): ‘Do you think putting on a skirt and heels is going to land you the job?!’ That was 5 years ago.” – A., 40, France.

@

5. “When women are successful in their professional field, they are referred to as ‘ukht rejal’, which means ‘sister of men’, in the sense that they are more manly.” – D., 30, Palestine.

@

6. “From a European Professor (ca. 55 years old) in Egypt: ‘Thank you for making coffee’ when actually I organised the entire scientific conference and the topic of my PhD project was closely connected to it. A male intern was appreciated for his ‘thoughts’ when he only asked an honestly rather ignorant question.” – K., 30, Egypt.

@

Women are also confined to their reproductive role and to the full and exclusive management of the domestic space with its devalued tasks:

7. “In administrative forms, when you are asked your profession and you are a housewife, you must choose ‘no profession’ even if you have diplomas, because you do not earn any salary.” – M., 61, France.

@

8. “On Fridays, when my husband and I go to my family for the weekend, my mother tells me: ‘Prepare some food for your husband, he is tired, he has just finished his week.’ But I worked as hard as he did! As if my job isn’t as tiring as his.” – R., 26, Palestine.

@

9. “When I wanted to apply for my master’s, I had to take permission from my eldest brother, as my father passed away (editor’s note: it is then the second closest man who decides). In a refusal tone he said ‘Why do you need a masters? Are you planning to work?’ A sarcastic question telling me I’m not allowed to work. As if my bachelors was just a degree to be kept at home and I wasn’t supposed to have career ambitions.” – B., 24 years old, Oman.

@

10. “’Why work when you can live and be treated like a queen?’ from a family member when they observed me taking my work too seriously and suggested that I could free myself from all work-related worries and stress by being taken care of by my husband instead.” – T., 26, Qatar.

@

11. “Remarks that are always turned into jokes: ‘You are going play the maid‘ meaning that you are going to cook.” – V., 44, France.

@

Finally, and all the more serious, women from minorities suffer double discrimination with remarks disguised as jokes:

12. “The ‘sense of humour’ of some colleagues who joke about me with an added layer of racism: “M., she doesn’t go to the hairdresser, she goes to the groomer.”- M., 30, Switzerland.

5. Have you felt an improvement in the way women are perceived/treated by men over the last 10 years?

The answers are mixed in both regions. The most pessimistic responses reflect a sense of immobility and polarisation of society:

“I am sadly not optimistic. I would have had a completely different future awaiting me, I missed out on so many great career opportunities, all because of people who have power over my life and truly believe it’s their right to.” – B., 24, Oman.

@

“Society is going to the extremes more: too liberal or too conservative. Speaking up is encouraged by social media platforms – but they are not available to all (poor people).” – D., 30, Palestine.

@

“Yes. And no. I still experience basic sexism from mainstream society as well as a professional glass ceiling. It is clear that very few men realise their privilege and are willing to share it with women – and the minorities around them, if they are white, straight and cisgender.” – A., 34, France.

@

There are, however, reasons to remain hopeful, particularly thanks to social media “with #MeToo (editor’s note: a movement that went viral on social networks in October 2017, giving a voice to victims of sexual assault and harassment), rape and pedophilia scandals that shed light on the submission imposed to women”(A., 40, France). Many campaigns make it possible to call out “harassment and sexual violence, especially in Egypt where most people are very active on Facebook” (K., 30, Egypt).

Regarding mentalities, sexist clichés are internalised by women, some of whom “are convinced that their place is not in a professional environment but in the kitchen” (N., 48, Switzerland). However, they are beginning to be seen as an equal partner in marriage which is “gradually perceived more as companionship, especially from the men’s point of view, rather than a means of preserving the family name” (T., 26 years, Qatar). The younger generation, meanwhile, is growing up with a better representation of roles:

“Children seem more open, even if they remain ‘conditioned‘ in many ways. My partner’s nephews and nieces don’t find it strange to see women playing soccer, but still have a very traditional image of marriage where it is the man that needs to propose and offer a ring.” – C., 32, Switzerland.@

@

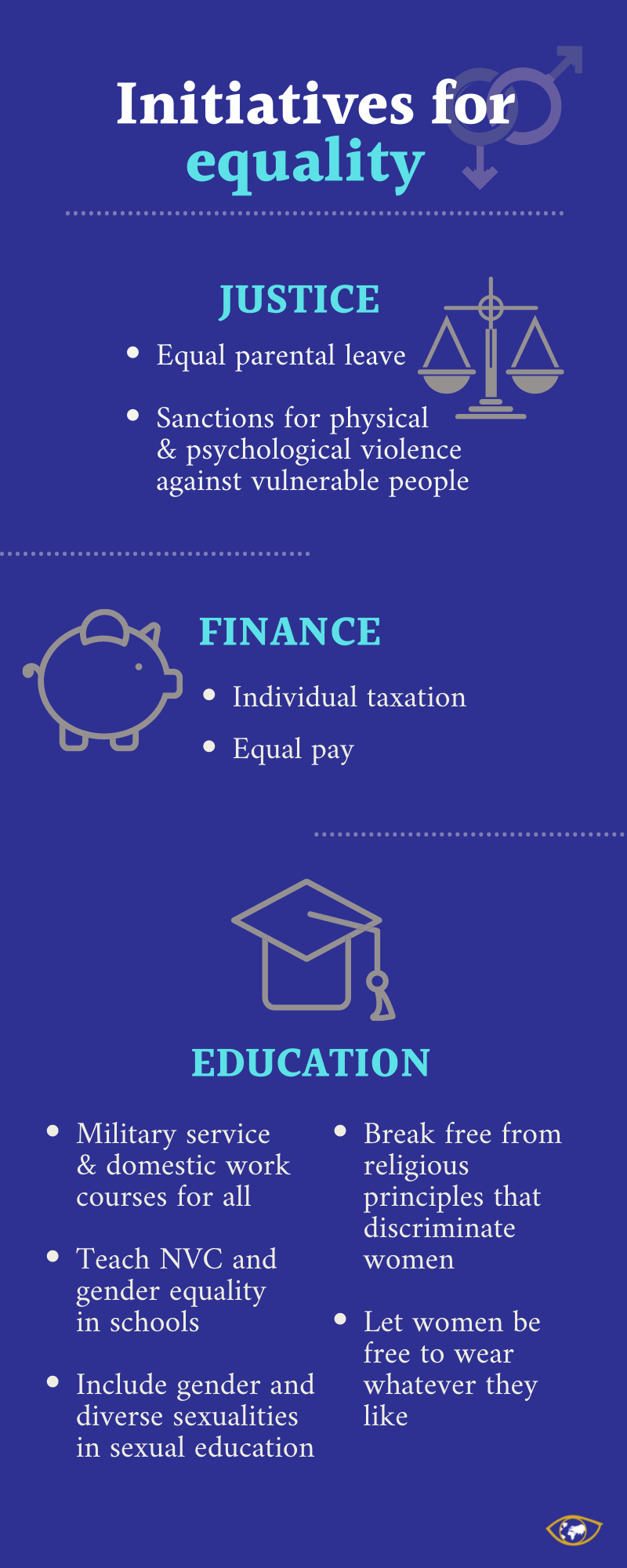

6. What measures can be implemented to promote equality?

Some excellent ideas came from all participants, with legislative proposals on parental leave, sanctions for violent behaviour as well as improved financial equality. Much remains to be done in the field of education, which is the foundation of society. Here is a summary of the contributions.

© emmy·in·the·mix

Thoughts

Although the overall perception of sexism seems less prominent in Europe than in SWA, almost all women reported having being harassed in the public space. They also reported being victims of micro-aggressions based on their gender: at work in both regions, mainly in the family circle in SWA and in sports and religious institutions in Europe.

After hearing these women’s experiences and suggestions, there is ground for optimism. People speak up. Many online campaigns targeting gender inequalities have been launched in recent years in Europe (#BalanceTonPorc, #MeToo) and in SWA with #NotYourHabibti (Not your sweetheart) in Palestine, #EnaZeda (Me too) in Tunisia, #MeshAyb (Not shameful) in Lebanon and #Ismaani (Hear me).

However, you have to prepare for a long battle. Caroline De Haas, a French politician, summarised it very well in an interview she gave for Rebecca Amsellem’s feminist newsletter:

“I was having lunch one day with Françoise Héritier (editor’s note: a French anthropologist and ethnologist) when she answered ‘no’ when I told her that everyone would be better off if we reached gender equality, both women and men. She told me that an egalitarian society is a more conflictual society for human relationships. As soon as power relations disappear, there are more arguments, frictions and therefore conflicts. I’m not sure it’s going to be easy. I’m even sure it is not. The very fighting for equality will lead to conflictual human relationships, in work relationships and in romantic relationships.”

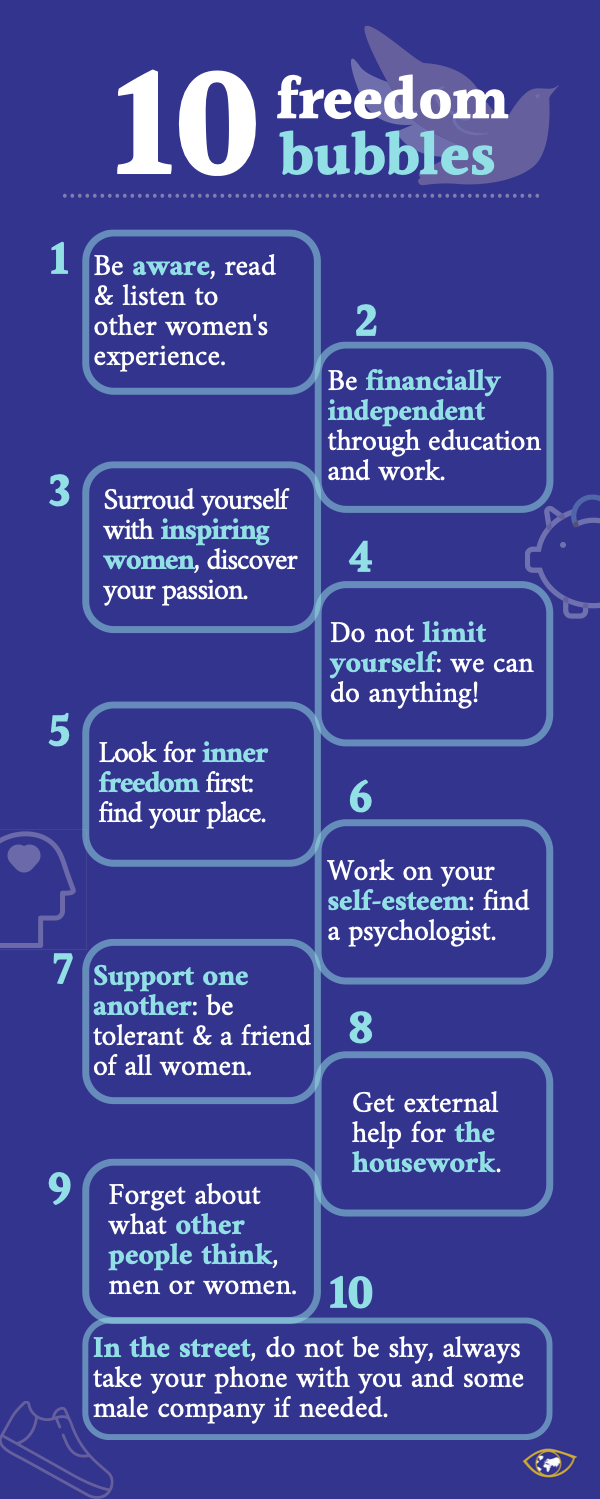

Fighting against millennia-old religious and cultural principles that are strongly intertwined, fighting against the very structure of both region’s deeply patriarchal society, fighting against one’s own brothers and partners… This is the price to pay for exercising one’s rights, eliminating violence and gaining real freedom. This battle will not be physical but social, educational and collective. It can be fought in several ways: below is some practical advice drawn from participants’ suggestions. This survey shows that by joining forces and resources, women are powerful and prepared to defend their rights. For them and for future generations.

© emmy·in·the·mix

This article also exists in French.

Resources

- Nawal El Saadawi: Women and Sex (1974)

- Jokha Alharthi: Celestial Bodies (2010)

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Dear Ijeawele, Or A Feminist Manifesto In Fifteen Suggestions (2017)

- Ahmar Bel Khat El Arid - أحمر بالخط العريض a Lebanese TV show that deals with the problems women face in conservative societies

Note: the illustration image was inspired by “Yolanda” from Chant Avedissian and “Meisje met de parel” by Johannes Vermeer.

Note bis: many thanks to all the women who have given me their time and trust – together we are stronger!